Abstract

As nonprofits explore options to scale their impact, for-profit subsidiaries present an intriguing but complex option. This article offers nonprofit leaders and funders a framework to evaluate whether a for-profit subsidiary is worth considering and presents a typology of three distinct models. While this structure can unlock growth opportunities for some organizations, success requires careful consideration of economic viability, organizational control, and mission alignment.

* * *

In 2019, OpenAI faced a critical challenge that would shape its future. Founded as a nonprofit with a mission to develop beneficial AI, the organization found itself in need of large amounts of growth capital to access the computational power and talent for its breakthrough research. The for-profit subsidiary it created allowed OpenAI to access billions of dollars in growth capital. It also contributed to a brief, but very public, ouster of its CEO, Sam Altman, simultaneously introducing the American public to some of the most notable pros and cons of this model.

While most nonprofit leaders will not be attempting to raise billions from investors to compete in hyper-competitive markets, some seeking access to growth capital and talent may wonder whether a for-profit subsidiary makes sense, and whether the complexity and risks are worth it. The path to an answer lies in clarifying motivations, asking three threshold questions, and carefully considering the implications of different paths.

Clarify your motivation

Like OpenAI, a primary motivator for most nonprofits considering a for-profit subsidiary is access to capital for sustainable growth. For-profits can access growth capital and talent that can be challenging or impossible for nonprofits to secure, such as equity funding.

A second motivation is risk mitigation, especially when an organization seeks to generate income that could put its tax-exempt status at risk. The IRS treats “unrelated business income” differently for nonprofits, taxing it differently and factoring it into decisions about an organization’s overall tax-exempt status. Some nonprofits establish subsidiaries to mitigate these risks.

A third motivation is to enhance organizational culture and capabilities. In many cases, for-profit organizations cultivate a market-oriented culture, which can contribute to speed, performance incentives, and partnership opportunities such as joint ventures. Nonprofits seeking these cultural assets might consider establishing or acquiring a for-profit subsidiary.

A for-profit subsidiary is one potential path to satisfying these motivations, and it is not right for every situation. Many successful nonprofits succeed without it. However, if these motivations are top of mind for you or your grantees, three questions should help you assess the wisdom and viability of this approach.

Ask yourself three questions

Three questions can inform decision-makers about the viability, trade-offs, and ultimate structure of a for-profit subsidiary.

Could a subsidiary access the amount and type of capital needed?

If the primary motivation is access to capital, consider the economics of the business that a subsidiary would host, and what type of capital it needs. A plethora of capital options exist for for-profit organizations, including debt (i.e., borrowed capital that is paid back over time, with interest) and equity (i.e., exchanging capital for an ownership stake in the business). Among other factors, the operating margins and growth potential of a business fundamentally determine what types of capital it can access and under what terms. For example, with commercial debt, lenders typically look for established businesses that demonstrate positive operating margins of 30% or more. With equity, venture investors seek out businesses that have a credible path to triple in size (i.e., 3X growth) over 5-7 years.

These thresholds create a high bar, and most nonprofits do not operate businesses that can clear them. For those that can, the type and amount of growth capital needed will inform the subsidiary approach, which leads to the next question.

What level of control over the subsidiary’s activities will the nonprofit need to assert?

All subsidiaries ultimately answer to their parent organization. However, different approaches to governance can provide varying degrees of operational control over the subsidiary. Organizations must carefully consider the degree of control they need to maintain over the subsidiary’s activities.

The answer often correlates with the nonprofit’s motivation in establishing the subsidiary and the type of capital it seeks. If the motivation is risk management, a high degree of control and coordination may be required. If the motivation is rapid growth, more autonomy may be required to attract capital and talent to the subsidiary. The answer to this question will inform key elements of the subsidiary governance model (e.g., board overlap, staff sharing, reporting structures) and leads to our third question.

What assets will animate the subsidiary’s activities, and who will control them?

Every organization relies on some combination of tangible assets (e.g., buildings, trucks) and intellectual property (e.g., brand, data, software code) to carry out its work. Nonprofits must consider which existing and future assets the subsidiary will need to access to carry out its work, and whether ongoing control of these assets is important. For instance, if the subsidiary is operating a building that is owned by the nonprofit or selling merchandise with the nonprofit’s logo and brand (both common subsidiary use cases), the nonprofit will likely want to retain control of those assets.

The answer to this question is important because it directly impacts access to funding, since most equity investors will expect their portfolio companies to control crucial assets in the event of a successful “exit” or sale to another organization. For example, if a nonprofit plans to establish a subsidiary that will operate a software product and generate valuable data as it grows, the subsidiary may not be able to access equity capital unless the parent nonprofit is comfortable with the subsidiary controlling these assets.

Consider subsidiary models in practice

Of course, every organization will have different answers to these questions. In practice, the data suggest three common themes, or typologies, that serve organizations with distinct priorities. Considering the characteristics of each can help organizations select an approach that aligns with its goals.

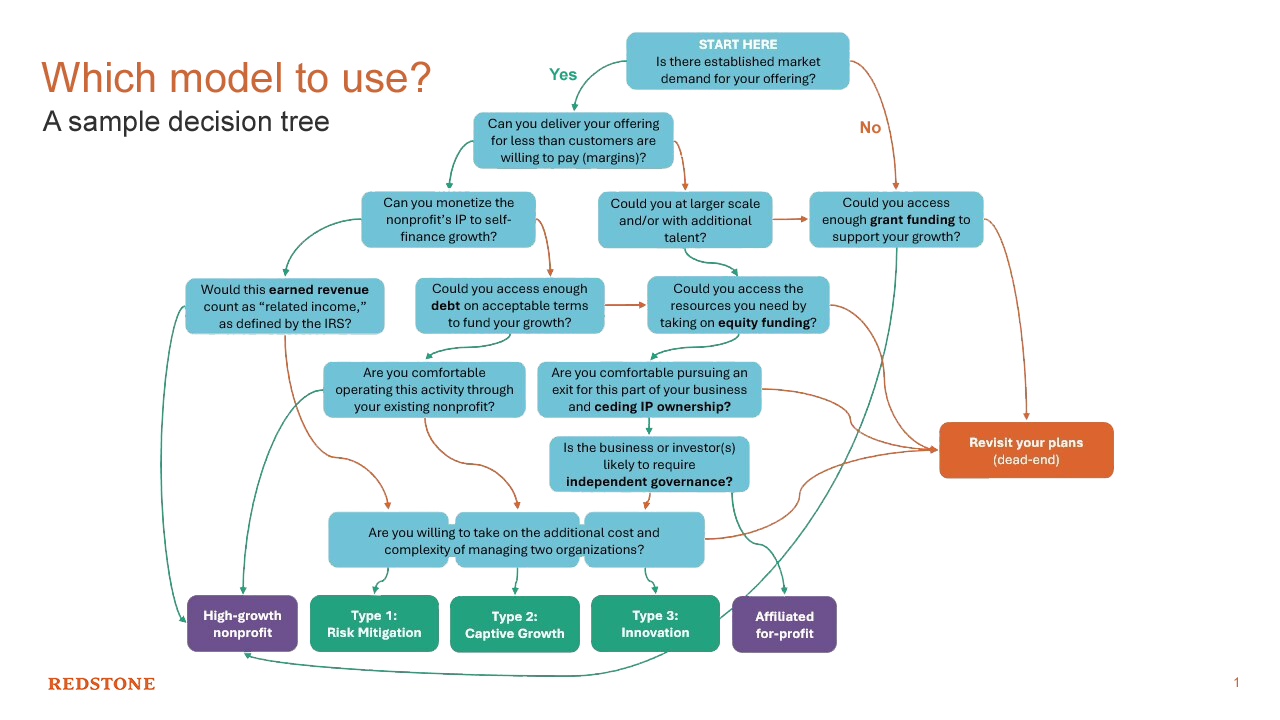

Figure 1: Capital sources, control, and asset ownership by subsidiary type

Type 1: Risk Mitigation

The first subsidiary model works well for organizations whose primary motivation is mitigating risk. These subsidiaries either have no capital needs or can meet their needs through borrowing (e.g., commercial debt), are tightly controlled by the parent organization, and often rely on assets that are – and always will be – controlled by the nonprofit parent. Examples include businesses such as merchandise sales that generate unrelated business income (e.g., museum gift shops or university apparel stores), and real estate and other capital- and risk-intensive projects.

Type 2: Captive Growth

Independent, profitable lines of business that complement a nonprofit’s mission are good fit for this second model. These subsidiaries may seek to access debt capital, can be tightly or loosely controlled by the parent organization, and often rely on the parent nonprofit’s assets. For example, Mozilla operates a profitable services business through a subsidiary of the Mozilla Foundation, and Pivot Learning acquired a for-profit professional learning business for K-12 educators (CORE) that it operates as a subsidiary.

Because these subsidiaries do not control crucial assets, they typically cannot access equity capital, making this model a poor fit for innovation. Which leads us to the third model.

Type 3: Innovation

The third subsidiary model works well for organizations that are motivated by accessing capital and talent for innovation. These subsidiaries are designed to eventually spin out of the parent organization. As such, they often seek equity capital and operate more independently. And, while they may rely on the parent organization for important things (e.g., back-office services, access to customers, and credibility), they typically maintain control of crucial assets, which leave with the subsidiary when it exits. Notable examples include university business incubators, tech accelerators, and holding companies.

Conclusion

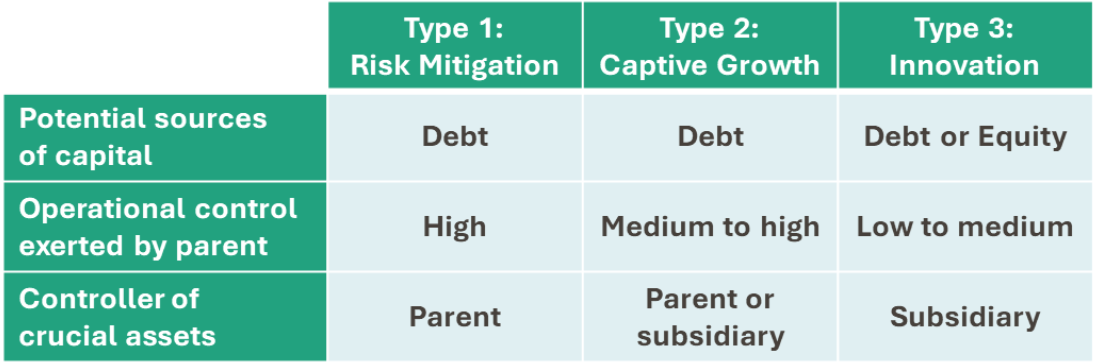

The decision to establish a for-profit subsidiary requires careful consideration of motivations, capital requirements, and expectations about decision-making control and asset ownership. The simplified decision tree in Figure 2 suggests a structured approach to assessing these factors and their implications for the resulting approach. We hope this provides some clarity. For many nonprofits, the path will lead to a dead-end, meaning a for-profit subsidiary is not the right approach. For those leaders who would like to explore the opportunity further, we encourage you to be in touch.

Figure 2: For-profit subsidiary model decision tree